- Home

- Norman Tasker

The Gladiators Page 2

The Gladiators Read online

Page 2

The furore that erupted in early 2013 certainly proved sports science has come a long way. I have no idea whether human growth hormone helps when it is injected into an elite athlete, or whether injected calf blood improves recovery. I know that to a Rugby League player of my vintage, it sounds weird and a little frightening. But is it really much of a surprise? We have heard stories off and on over many decades about people beefing themselves up with performance-enhancing drugs. It used to be anabolic steroids that were the popular choice. Now it seems the range of available assistance is much more sophisticated. And there’s the rub. The more things get banned, the more sophisticated the next drug will be. Clever biochemists are always going to get ahead of sports administrators when it comes to complex performance enhancement, and the products produced will keep stretching the limits of what is manageable. In all likelihood they’ll just get more dangerous. I don’t know what the answer is. But there are a few things I do know, and one of them is I find it hard to blame the young players who get led into this sort of thing.

I consider my own career. I was a little bloke, and I took a fair bit of punishment. I would have given anything to be able to bulk up. But all we could do in those days was drink a lot of milkshakes and eat a lot of bananas. Even weight training was in its infancy, and the quick blokes in the backs were often told it was bad to use weights because they would slow you down. So we stayed light and nippy and got bashed up a lot. If someone then had said to me that this pill or that injection would help me put on weight and build some power, what would my reaction have been? I probably would have looked at the maths first. If a bit more weight and power meant a big contract, I reckon I would have had a lot of trouble saying no. I think that is probably happening today as well. And because it is all cloak-and-dagger stuff, the vulnerabilities that the Crime Commission talked about, with criminals offering drugs and hooking players into match fixing, become possible.

In an ideal world we would rid sport of drugs altogether. Sport in my time was a relatively pure thing, and barring the odd incompetent referee, games were won and lost on the merits of the players. But it’s not an ideal world. The reality is you don’t have to look very far to realise that drug use in sport is everywhere. Recent revelations about cycling proved that at least seven Tour de France events were powered by drugs. Olympic Games stretching back generations have been found to be tainted, and especially among the very best athletes. Sport administrations just can’t keep up. There is also the question of how much resolve administrators have. If big drawcards are sprung, are officials going to ban them for two years? I doubt it. There is too much money at stake, and money, of course, is at the root of all of sport’s evils. So the question to be asked, I believe, is what is practical? What is practical not in the pure environment that we would like to have but in the enviroment that actually exists? The final question, I suppose, is whether performance-enhancing drugs that are proved safe should be legal.

The undeniable truth is that vices seem to be popular. Every effort has been made to deter people from smoking, but they still do it, often at great cost. America tried to ban alcohol and triggered one of the greatest illicit businesses in the history of the world. Gambling is under constant fire from governments and others, yet it is has never been more popular. And herein lies the next big problem. It has been determined that match fixing in soccer is rife on an international scale. The Crime Commission in Australia has said that all sports are vulnerable here.

Yet every time you turn on the television to watch sport, the gambling ads are everywhere. It has never been easier to get a bet on, and betting on humans is the current big thing. It has been proved that most match fixing is triggered by gambling syndicates and organised crime. But will sport give up the millions that gambling advertising brings them? I think not. The bottom line is that sport these days is big business. Big business revolves around big money, and big money will always bring its issues. In a way, Norm Provan and I were very fortunate.We played in an era when Rugby League was a game with no strings attached, and sport was something you did for fun. We loved it. We still love it. But the game is not the same, and we don’t kid ourselves otherwise.

2

THE MORE THINGS CHANGE . . .

THE HIGH MOMENTS OF Rugby League football follow a natural order. If it’s intensity you want, State of Origin football is your thing. The entrenched rivalry between New South Wales and Queensland demands no-holds-barred confrontation as a matter of course. Then there are Test matches. They have an aura of their own—though perhaps not at the level they once did—because they bring nation against nation, and they represent the ultimate recognition for any player. But when it comes to the raw emotion of extended tribal conflict, nothing rivals a grand final.

Comparatively few players get to play a grand final. Those who do cherish the experience for life. For those players who actually win one, it remains forever a unique high point of their sporting existence. Norm Provan played in ten grand finals and won the lot. He was captain–coach of a famous St George team for the last four of them, so he knows a thing or two about what works and what doesn’t.

For Arthur Summons, grand finals have always held particular interest. He played three in a row for Western Suburbs in their classic encounters with St George. Wests lost all three as Saints powered on to their eleven straight titles between 1956 and 1966. Move forward to 2012, and the grand final at Sydney’s Olympic Stadium has special relevance. Summons still feels the pain of the 1963 grand final, immortalised in the photograph that captured the two captains, Summons and Provan, as they left the mud-swamped Sydney Cricket Ground. Summons believes to this day that Wests got a raw deal from referee Darcy Lawler, and the perceived injustice of it has never left him.

Now, as the 2012 combatants parry and thrust in pursuit of the trophy that bears their image, both Summons and Provan feel the emotion. The decider between the Melbourne Storm and the Canterbury Bulldogs was always going to be an absorbing contest. The Bulldogs had come from nowhere under their new coach, Des Hasler, to be serious contenders. The Storm were seeking redemption, having had two recent premierships stripped from them for salary cap breaches, and having been ruled out of the 2011 contest for the same reason. Summons can empathise with the Melbourne Storm and the pain of having hard-won premierships taken from them. Provan studies the artistry of Billy Slater and Cooper Cronk, and his mind instantly goes back to a time when his ‘boys’, Reg Gasnier and Graeme Langlands, were working their way to Rugby League immortality.

Summons is taken with the different emphasis of the grand final teams. Melbourne are efficient to a T, blocking Canterbury’s considerable attacking potential with a defensive pattern that might have been constructed on a chess board. In attack they bide their time, cover every angle, wait their chance.When they strike, they do so with deadly precision. Canterbury, on the other hand, stick to a game plan that has worked for them all season. They look for the dynamics of their fullback Ben Barba. They bring their powerful centres Josh Morris and Kristian Inu into play at every opportunity. Nothing they can do surprises the Storm, and the defensive wall holds. At first opportunity, Summons is led to inquire of his old mate Provan,‘What would Gaz have done with the opportunities those centres had?’ Provan’s reply is instant, and to the point: ‘He would have bolted.’

To these warriors of another time, the link between past and present is a tether that twists and stretches in remarkable ways. The cavalcade of champions that has paraded before them over the past 50 years is recognised and admired. The evolution, or revolution, that the game has seen has been a constant source of amazement, but it is accepted for what it is, on the basis that change is inevitable in any walk of life. But the standards and the ethos that drove Provan and Summons are not diminished by time. Their respect for their era remains fierce. Provan had in his team three players—Gasnier, Langlands and the irrepressible John Raper—who are revered today as immortals of the game. Summons was captain–coach of the f

irst Kangaroo team to defeat England in a series in Britain. Gasnier, Langlands and Raper were not the only champions to make that team perhaps the greatest of all Kangaroo sides. For both of them, the triumphs of those days remain etched in the mind.

ARTHUR SUMMONS

I admire a lot of the things that make modern football what it is. I certainly admire the athleticism of the modern player, and raw skill is something that rises to the top in any generation. Progress is inevitable, and it stands to reason that many things have improved since my day in the way footballers are developed and prepared.

But that doesn’t mean there is not a lot about the modern game that is off track. The regimentation of the way the game is played, a certain lack of flair and initiative in an era that concentrates on eliminating risk, are part of the downside of today’s game. And it is certainly not right to deride the football of my time as amateurish or old-fashioned. By today’s standards it probably was more amateur than professional, but we worked very hard according to the standards of the time. It was very important to us, and we produced players whose skills would stand in any era.

The bottom line, I suppose, is that Rugby League was a great game in my day and is a great game today, despite being very different. I’m just glad people still ask me what I think. Without that photo and the trophy that followed it, I think I might have been forgotten a long time ago. But 50 years on I still feel part of the game and I am grateful that I’m still involved. And I’m grateful too that I played in a wonderful era in both Rugby codes, when sport was something you got into for fun, and for the mateship that lasts a lifetime.

NORM PROVAN

I still pinch myself when I look back on the time I had in Rugby League. I was lucky to fall into a team and an era that will never be matched. I started with St George in 1950 and I finished in 1965, and I loved every minute of it. I thrived on the training. I loved running around the bush at Carss Park or on the sandhills near Cronulla.

St George in those days had marvellous administrators who kept the club supplied with outstanding players, and there is no doubt that was the reason we won eleven premierships on the trot. Some of those players—Raper, Gasnier, Langlands for certain, maybe Harry Bath too—were better than anybody who has come since. Andrew Johns, Wally Lewis, Arthur Beetson and players like that were all greats, but I wouldn’t put them ahead of the players we gathered in the one team through the early 1960s.

Like Arthur, I too am very happy that the Gladiators photo and the NRL trophy have kept us in the spotlight and allowed us to remain close to the game. But I believe there is a lot about the game today that needs attention if we are going to stay on top. They said of the St George team of my time that we had too much ‘bash and barge’, and they did away with the unlimited tackle rule because of it. But I believe there is more bash and barge today—they call them hit-ups now—than there was in my day, when getting the ball to Gasnier and Langlands and those blokes was always a priority because we knew they would do marvellous things with it. Rugby League should be a running and passing game. It seems to me there is not as much of that today as there should be. Don’t get me wrong, it is still a great game. But I can’t get from my mind the vision of Gasnier flashing up behind me screaming ‘Sti-i-i-i-cks’ at the top of his voice, looking for the pass and running like the wind. I don’t see anywhere near as much of that today as I think we should.

•

Grand finals come and go, but to Norm Provan and Arthur Summons there is now a perpetual link that goes beyond the recollection of their contests of long ago and the trophy that celebrates them. Each year they present the Provan–Summons medal to the popularly voted player of the year. In 2012 it was the electrifying Canterbury fullback Ben Barba. Year by year, it often involves a grand final player, and it always involves a champion on the rise. Talking to these young achievers, watching them develop, sharing the thrill of their efforts and their triumphs, is a rare privilege for two champions of another age.

3

AN IMAGE FOR THE AGES

IN THE HOURS AFTER the 1963 Rugby League grand final, the newsroom at the Sun-Herald office in Sydney was much like it was on any Saturday night. The hustle and bustle were everywhere as editions rolled out one after another and fleets of trucks gathered in the streets outside to take half a million papers to all parts of the state. Reporters clattered away on typewriters, editors and sub-editors pored over their work and planned layouts, and on the floor below banks of Linotype machines made a terrible din as they turned pots of molten metal into lines of type. This was an age before computers. Everything took time, and the urgency of the workers and the precision of their teamwork were a matter of routine.

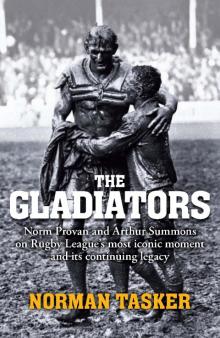

John O’Gready, a photographer with a wild side to his nature and flair to match, had patrolled the Sydney Cricket Ground sideline all afternoon as St George and Western Suburbs did battle. It had been a miserable day, and the SCG had taken such a pummelling from three games of football that afternoon that it looked like an oyster lease. Robert Menzies was still Prime Minister, and Australia was such a conservative place that O’Gready did his afternoon’s work dressed in a suit. His shoes were clogged with mud and his trousers splattered, but he covered hundred of metres up and down the line looking for the perfect picture. Somewhere around 4:37 p.m., he got it. Full time had been called, the Saints had won again, and as the players traipsed from the field O’Gready found his magic moment.

Long before the arrival of the digital technology that allows photographs to be produced and transmitted in seconds, getting a photo into print was a tortuous process. The practice was to have a car and driver waiting to rush the film back to the Herald office in Ultimo. O’Gready made the delivery without any real idea of what he had, and the driver whipped the film over to the processing staff. When O’Gready later caught up with his negatives back at the darkroom, he picked out eight or so that he thought were the best of the day, printed them and passed them on to his editors for judgement. O’Gready’s favourite was a shot of a toothless Norm Provan caked in mud. Provan’s eyes and a couple of remaining teeth jumped from a black face, but the smile was clear and the emotion obvious. It was a powerful photo.

As O’Gready started to sell his choice, his pictorial editor, Graham Wilkinson, took one last look through the reject pile. He grabbed the photograph of the two captains in momentary embrace and said, ‘This is the pic.’ On the editorial floor, Jack Percival, one of the senior operatives of the time, went so far as to say it was the second-best photograph he had ever seen. In his mind the only one to beat it was the one of Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima in World War II, perhaps the most published news picture of all time.

Wests captain Arthur Summons had gone to Provan to congratulate him, as captains did at the end of the game. As Provan saw Summons coming towards him, he ripped off his jumper, baring the shoulder pads that gave the photograph its image of armour and lent weight to its eventual ‘Gladiators’ tag. Provan recalled being a little taken aback by the short exchange with Summons. Neither of them had any idea that O’Gready was lurking to immortalise it. The embrace was fleeting. O’Gready had only a couple of seconds to grab it, and the light was terrible. But just as the two captains came together, the clouds split momentarily, and a shaft of light hit the two muddied figures like some heavenly spotlight. Thus was born an image for the ages.

It was celebrated as depicting all that was fine about sport, and Rugby League in particular. A winner and a loser in recognition of each other; the big man and the little man on even terms; the spirit of a battle hard fought in tough conditions, yet celebrated for the joy of it; the mateship; the camaraderie of a hard game. The photo appeared next morning on page 3 of the Sun-Herald. O’Gready was disappointed it was not on page 1. The reality is that he was very lucky to get it.

In the 50 years since that photo was taken, Summons and Provan have revelled in the involvement it has maintained for them in a game to which they devoted a good part of their youth. It has

brought them together as firm friends. Yet they still laugh about that famous embrace—and what they were actually saying.

ARTHUR SUMMONS

I don’t know that I have ever been more shattered than I was in the moments after that defeat. Wests had played grand finals against Saints in the previous two years as well and lost, and we figured we were a real good chance this time, since we had beaten them twice in the competition rounds and once in a semi-final. But we had a shocking deal from referee Darcy Lawler in that game, and I was furious. I went to Norm to congratulate him, but I don’t think I was very generous in what I said. It was something like, ‘You were lucky to get away with that, thanks to that bloody referee,’ or words to that effect.

It didn’t mean I lacked respect for what Saints had achieved. They were a fantastic side, and on a dry day we probably would not have got as close to them as the 8–3 result of that afternoon. And Norm himself was magnificent. He seemed to rise a couple of levels in grand finals. He was fabulous. But our conversation was more strained than the photo and the popular interpretation of it would suggest. I’ve mellowed since, of course. I now look upon that moment as one of the greatest of my life, given the way it was captured and what that has meant since.

The Gladiators

The Gladiators